In 1957, Achille Castiglioni walked into a Milan design studio with a tractor seat and a bicycle saddle. His colleagues thought he’d lost his mind. Five years later, his Mezzadro and Sella stools were redefining what furniture could be. This was Castiglioni’s gift: seeing extraordinary possibilities in ordinary objects that everyone else ignored.

The Architect of Everyday Miracles

Born in Milan in 1918, Achille Castiglioni didn’t just design objects — he performed acts of transformation. While his contemporaries sculpted forms from scratch, Castiglioni prowled hardware stores and auto junkyards, collecting industrial components like treasures. A car headlight became the Toio lamp. A fishing rod inspired the Arco’s arc. This wasn’t recycling; it was alchemy.

The youngest of three brothers, Achille studied architecture at Milan Polytechnic, graduating in 1944 into a war-torn Italy that needed everything rebuilt. But instead of designing monuments, he focused on the microscopic: light switches, door handles, ashtrays. “Start from zero,” he’d say, questioning why things looked the way they did.

- Born: February 16, 1918, Milan

- Died: December 2, 2002, Milan

- Education: Architecture, Politecnico di Milano (1944)

- Philosophy: “Design is not about form, but about the problem”

- Superpower: Making ready-mades feel inevitable

The Brothers Castiglioni: A Design Dynasty

Achille’s career began in partnership with his brothers Livio and Pier Giacomo. Their Milan studio became a laboratory where industrial design met Italian wit. When Livio left in 1952 to pursue urban planning, Achille and Pier Giacomo continued as a duo that would define Italian design’s golden age.

The brothers worked like jazz musicians — Pier Giacomo laying down structure, Achille improvising wild solos. They’d argue, sketch, build prototypes in their studio filled with found objects and failed experiments. When Pier Giacomo died suddenly in 1968, Achille lost not just a brother but his creative other half. Yet he continued, carrying their shared vision forward for another 34 years.

Their collaboration produced icons: the Arco lamp (1962) that brought street lighting indoors, the Taccia lamp (1962) that looked like a glass bowl upside-down, the whimsical Snoopy table lamp (1967). Each piece solved problems with such elegance that the solutions seemed obvious — afterward.

The Ready-Made Revolution

Castiglioni’s genius lay in recognizing that good design already existed — it just needed recontextualization. The Mezzadro stool (1957) took a tractor seat, added a steel stem and wooden base, creating seating that was both agricultural and sophisticated. Critics were scandalized. The public was delighted.

The Sella telephone stool (1957) went further: a bicycle seat on a steel rod that forced dynamic sitting. You couldn’t slump on Sella — you perched, ready for action. It was uncomfortable for lounging, perfect for quick calls. Form followed function so honestly it hurt (literally).

The Art of the Found Object

- Toio lamp (1962): Car headlight + fishing rod = adjustable lighting

- Allunaggio (1966): Industrial reflector bulb = landing on the moon

- Primate (1970): Garden tools + ingenuity = multipurpose implements

- Gibigiana (1980): Mirror + mechanics = light that draws on walls

- Philosophy: “Why design what already exists perfectly?”

The Arco Lamp: Bringing the Street Inside

In 1962, the Castiglioni brothers faced a problem: how to light a dining table without ceiling fixtures? Their solution — the Arco lamp — became the most copied design in history. A Carrara marble base (65 pounds of it) anchored a stainless steel arc that reached eight feet across space, dangling an adjustable dome exactly where needed.

The genius was in the details. That hole in the marble base? For a broomstick, so two people could move it. The arc’s telescoping stem? Three sections for precise positioning. The dome’s perforations? To prevent overheating while creating ambient uplighting. Every element solved multiple problems.

Arco succeeded because it was a system, not just a lamp. It brought street lighting’s long reach indoors, freed dining from fixed ceiling points, and created sculpture from function. When FLOS put it into production, they thought it might sell hundreds. Six decades later, it’s still in production, still revolutionary.

Beyond Furniture: The Complete Designer

Castiglioni designed everything: exhibitions that felt like theater, stereo systems that looked like architecture, even a beer tap that became sculpture. His RAI radio headquarters in Milan (with brothers) proved architects could think small — door handles that felt perfect in the hand, light switches placed exactly where fingers expected them.

For Brionvega, he created the RR126 stereo (1965) — a radiophonograph that folded into a minimalist box, then opened like a flower to reveal turntable and speakers. It wasn’t just playing music; it was performing architecture. For Alessi, he designed the Sleek ashtray (1989) that used gravity to hide cigarette butts, making even smoking elegant.

His approach was always investigative. Designing a switch for VLM? He studied how fingers approach walls in darkness. Creating museum exhibitions? He watched how people moved through space, then designed displays that guided without forcing. Everything started with observation, ended with revelation.

Teaching the Castiglioni Way

From 1969 to 1993, Castiglioni taught industrial design at Turin Polytechnic, turning lectures into performances. He’d arrive with shopping bags full of objects — a perfectly designed paperclip, a badly designed corkscrew, anonymous industrial pieces that solved problems beautifully. “Look how intelligent this is!” he’d exclaim, showing a humble coat hook.

His teaching method was Socratic with props. Why does a chair have four legs? What if it had three? One? None? He’d make students redesign objects they took for granted — salt shakers, doorknobs, pencils — stripping away assumptions until only problems remained. Then, and only then, could design begin.

Students remember his joy in discovery. He’d demonstrate how a simple spring could become twenty different objects. He’d show slides of anonymous industrial design — conveyor belts, laboratory clamps — with the enthusiasm others reserved for Picasso. Design wasn’t about ego; it was about intelligence made visible.

The Wit of Function

Castiglioni proved that functional didn’t mean humorless. His designs winked. The Mezzadro stool said “I’m a tractor seat” while being perfectly urban. The Snoopy lamp’s marble base and metal shade created a character — hence the name. Even serious designs like the Luminator (1955) had personality: a bare bulb on the thinnest possible stem, like a flower drawn by a child.

This wit wasn’t superficial but structural. The Allunaggio lamp used a bare industrial bulb — the kind used in Milan’s Galleria — mounted on a folding base. Its name means “moon landing,” joking about its lunar appearance while seriously providing perfect task lighting. Humor made function memorable.

- Spalter vacuum (1956): Made cleaning look like skiing

- Sella stool message: “Sitting is temporary”

- Joy clock (1989): Numbers that tumbled like acrobats

- Cumano table (1978): Folded like origami, stored like air

- Design motto: “If you’re not having fun, you’re doing it wrong”

The Milan Method Goes Global

While Scandinavian design whispered and German design commanded, Italian design — led by Castiglioni — conversed. His objects started dialogues: between industrial and domestic, between serious and playful, between problem and unexpected solution. This approach influenced generations of designers who learned that intelligence could smile.

Major manufacturers lined up: FLOS for lighting, Zanotta for furniture, Alessi for objects, Knoll for international distribution. Each collaboration spread the Castiglioni method worldwide. By the 1980s, you could find his anonymous designs everywhere — the Kraft mayo spoon, the Ideal Standard faucet — without knowing their author. He preferred it that way.

Museums collected frantically. MoMA owns 14 of his designs. The Triennale di Milano dedicated entire exhibitions to his work. But Castiglioni was most proud when his designs became invisible through ubiquity — when people used his objects without thinking about design at all.

Living With Castiglioni Today

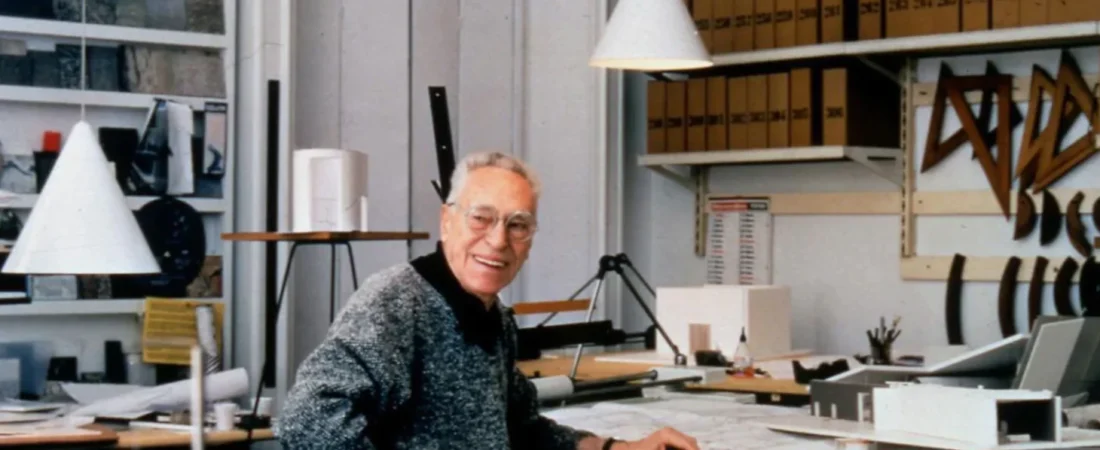

In his 1960s Milan apartment (now a museum), Castiglioni lived surrounded by his experiments. Prototypes cluttered tables. The Arco lamp lit family dinners. The Mezzadro stool served as extra seating. He tested everything on himself first — if it didn’t improve his life, why inflict it on others?

Today, his designs feel more relevant than ever. In an age of planned obsolescence, his objects last decades. While smart homes complicate, his solutions simplify. The Arco lamp still solves the same problem, still looks contemporary, still costs a fortune (authentic ones fetch $3,000+) because good ideas don’t age.

FLOS, Zanotta, and Alessi keep his designs in production, maintaining original specifications. The Fondazione Achille Castiglioni preserves his studio/museum in Milan, where visitors can see his collections of anonymous objects, his design process, his joy in discovery. It’s a shrine to curiosity, not ego.

The Castiglioni Legacy

Achille Castiglioni died in 2002, but his influence grows. Young designers study his method: observe problems, question assumptions, find solutions in unexpected places, add wit without subtracting function. His greatest lesson? That design thinking applies to everything — from city planning to paper clips.

His objects endure because they’re ideas made physical. The Arco lamp isn’t just lighting; it’s the concept of bringing street lighting indoors. The Mezzadro isn’t just seating; it’s the recognition that industry already solves problems beautifully. Each design teaches us to see differently.

“Start from zero,” he taught, but he rarely did. Instead, he started from observation, from curiosity, from the radical notion that good design already surrounds us — we just need eyes to see it. In hardware stores and junkyards, in anonymous industrial catalogs and forgotten patents, Castiglioni found magic. Then he shared it with the world, one transformed tractor seat at a time.